By Dr Innes McCartney, Nautical Archaeologist

As the world’s first battle cruiser, HMS Invincible was by any measure a revolutionary and important warship. All big-gun armament and turbine propulsion marked her out as one of the ships that led the dreadnought revolution. Her destruction at the climax of the Battle of Jutland, along with all but six of her crew of 1,031 was captured by photography and represents some of the most haunting images of the First World War. As a shipwreck, her remains too are no less stirring and emotive, while providing a valuable archaeological resource from the era of the dreadnoughts.

The actual clash of the two battle fleets at Jutland lasted only a few minutes before the heavily outnumbered German High Seas Fleet retired. But during this action HMS Invincible was the lead British ship. At the short range of 9,000 yards she was targeted by her enemies and just like the two other battle cruisers HMS Indefatigable and HMS Queen Mary destroyed earlier in the battle, she blew up in a massive conflagration. The explosion engulfed the entire ship and sunk it in less than a minute, giving little chance for any of her crew to escape.

Of the six survivors, the marine, Bryan Gasson had the most remarkable of escapes. He was actually inside HMS Invincible’s ‘Q’ gun turret when it was struck by a shell and hurled into the sea:

“Suddenly our starboard midship turret manned by the Royal Marines was struck between the two 12-inch guns and appeared to me to lift off the top of the turret and another from the same salvo followed. The flashes passed down to both midship magazines…The explosion broke the ship in half. I owe my survival to the fact that I was in a separate compartment at the back of the turret”

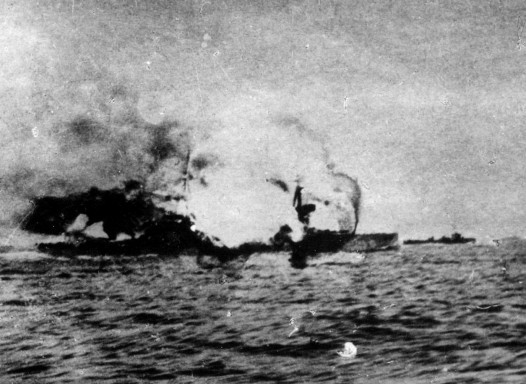

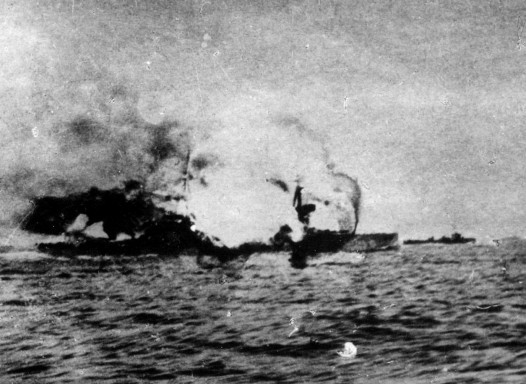

HMS Invincible’s centre magazines explode (IMW SP2468)

The two centre turrets of HMS Invincible had exploded, breaking the ship in two. A photograph showing the exact moment the ship exploded has survived and it shows not only the explosion in the centre, but also the ghastly sight of a massive jet of flame emitting from under where the fore turret was situated. In reality it means that the centre magazines had ignited and at the moment the photo was taken the entire insides of the ship most likely resembled a furnace. All of the six survivors worked in external parts of the ship. No one inside survived.

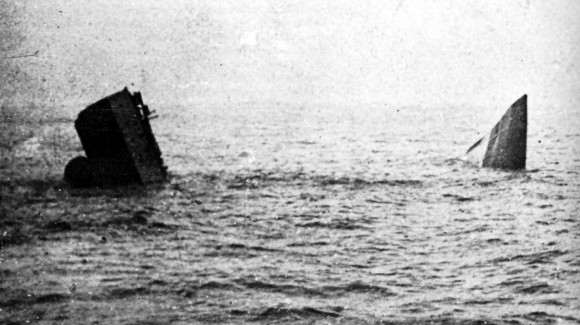

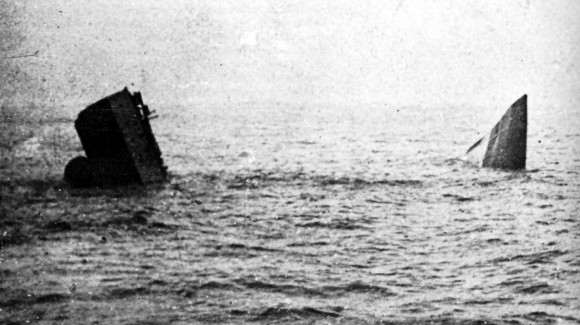

Within moments of the explosion, two halves of this proud ship jutted upwards from the seabed of the North Sea in an ugly reminder of what happens when battleships blow up. The two halves of the ship stayed afloat for nearly 24 hours before falling to the seabed, entombing the 1,025 casualties, already beginning to be mourned back in Britain. And so they remained until 1991 when a British expedition marking the 75th anniversary of the Battle of Jutland found the wreck.

HMS Invincible sinks (IWM SP2470)

I first dived the wreck of HMS Invincible in 2000 and was able in the following years to thoroughly survey her with further dives and a Remotely Operated Underwater Vehicle (ROV). The forward half of the wreck is upside down and mostly sealed into the seabed. The stern section is upright. Between the two halves lies much of the internals of the ship including machinery, boilers, and at least one turret sleeve which probably once held Bryan Gasson’s ‘Q’ turret.

Q turret barbette of HMS Invincible (Innes McCartney)

The most iconic and emotive remains of the wreck of HMS Invincible are her turrets themselves. On the stern half of the wreck, the guns of ‘X’ turret, (now without the turret roof) still point to starboard as if ready to fire at a long departed enemy. The massive 12-inch naval guns are all the more impressive because they are HMS Invincible’s and it is difficult to describe the sensation of actually seeing these for the first time. The signs that the ship was heavily engaged in combat are everywhere to be seen. Of particular interest are the shut breech doors inside ‘X’ turret, showing that the ship was about to, or had just fired when she blew up.

A shut breech door inside X turret of HMS Invincible (Innes McCartney)

From the witness accounts it is known that ‘P’ and ‘Q’ turrets fell out of the ship during the explosion. The gun turrets, or rather their remains, were found on the seabed several metres behind the track of the ship, both are upside down and can be distinguished because ‘P’ turret retains only one of its two guns. Minor details abound on the Jutland wrecks and the impact of human agency can be seen wherever chooses to look, such as the partially opened escape hatch which can clearly seen on ‘P’ turret. A stark reminder of the loss of life.

With the passing recently of the last of the Great War’s sailors, it is important that we don’t forget the men of the Grand Fleet. The wrecks of the Battle of Jutland recall this era more vividly than anywhere else I have surveyed. In war’s unfathomable lottery, marine Bryan Gasson’s survival from ‘Q’ turret was somehow made all the more remarkable by the discovery of his battle station in 2000. By the side of the turret lies one of the rounds which would have been the next Gasson’s team would have fired at the enemy if their proud ship had survived. After surviving the war, Gasson became school teacher and at the age of 85 was presented to the Queen at the commissioning of the aircraft carrier HMS Invincible in 1980.

The gun muzzles of HMS Invincible’s X turret (Innes McCartney)

Although I have surveyed the wrecks on six occasions I know that only the surface has been scratched of what the Jutland wrecks can offer archaeologically and historically. So their protection is of the utmost priority. Sadly there is much evidence of commercial salvage among many of the wrecks so far discovered. Some are now barely recognisable. It is my sincerest hope that the UNESCO 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage will in time, offer protection to these remarkable monuments to the battle fleets of the Great War and the brave men who sailed in them.

Innes McCartney has partaken in and led six expeditions to the wrecks of the Battle of Jutland. He found three new sites and produced the C4/Discovery/ZDF film “Clash of the Dreadnoughts”. He specialises in investigating, researching and interpreting the remains of 20th Century shipwrecks.

Bournemouth University

Bournemouth University