By Dr Richard Berger, Associate Professor, The Media School.

Tucked-away behind the Fiveways pub in Winton, is Fampoux Gardens. Built by ex-servicemen in 1922, the garden has at its centre, a sundial. This modest memorial is inscribed with the words:

“On March 28th, 1918 the enemy launched a big attack at Fampoux. The Hampshires refusing to be driven back, the enemy received a serious defeat”.

On the British Pathé website, you can watch an eerie, flickering film of the survivors of that battle, from the Royal Hampshire regiment, leaving their ship at Southampton docks in 1919. The Great War (1914 – 1918) was the first major conflict to be documented by the relatively new medium of film.

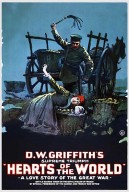

Cinema was barely a decade old when the conflict began, but by the time it had finished, filmmaking had matured to an extent that it was being used to create a rich (and controversial) visual record which continues today. Released before Armistice Day in the November, D. W Griffith’s Hearts of the World (1918) was so controversial in its portrayal of the German troops, it delayed the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. That same year, Charlie Chaplin’s Shoulder Arms was a more sensitive attempt to present the war through a soldier’s eyes – Chaplin continued to raise money for service charities. Other films, such as King Vidor’s The Big Parade (1925) tried to convince audiences that it was the USA who had brought the war to an end.

It was All Quiet on the Western Front (1930), which established the war film as a serious genre. It starred German and Austrian veterans and it marked the point where patriotism was turning into circumspection. A rising star of Germany’s new Nazi party, Joseph Goebbels, reportedly let off a stink bomb during a screening. The war films of the 1930’s had an American bias, largely because Hollywood was now the dominant force in cinema. Films such as A Farewell to Arms (1932, remade in 1957) and Ever in my Heart (1933) depicted an American soldier falling in love with a British nurse, and an American woman marrying a German, respectively.

As Europe was once again consumed by a second world conflict in the 1940s, cinema revisited the Great War as means to comment on the on-going one. Howard Hawks’ Sergeant York was a cynical piece of propaganda, which became an effective recruiting tool. In the UK, Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943) so enraged Winston Churchill, for its even-handed treatment of both British and German troops, he tried (unsuccessfully) to have it banned. Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957) told the story completely from the French point-of-view, and in doing so managed to encapsulate the anti-war fervour which was now gripping America – by now locked-in another conflict in Vietnam.

T. E Lawrence may have met his end on Dorset’s roads in 1935, but David Lean’s treatment of him in Lawrence of Arabia (1962) is probably the most well known First World War film. After Richard Attenborough’s adaptation of the satirical stage-show Oh! What a Lovely War in 1969, the genre declined as cinema moved onto the Second World War, and the Korean and Vietnam campaigns for inspiration.

Television took up the baton, and in 1986, the BBC series The Monocled Mutineer didn’t hold-back in its depiction of the events surrounding the very real Percy Topliss – an infamous deserter and conman. The highpoint of First World War satire came from an unexpected quarter: the final series of a historical comedy – which until then had preferred slapstick and absurdity to satire. Blackadder goes Fourth (1989) lampooned the stupidity of the British officer class, and the mindless futility of war. Underneath the laughs lurked some sharp observational truths: in his four years in France, Field Marshall Haig never once visited the trenches, or the wounded. His officers really did have nothing but beating sticks to protect themselves, and in one day alone (June 30th, 1916), 30,000 British troops were mown-down while walking slowly towards German machine guns. Blackadder skilfully negotiated these historical realities, building-up to one of the most moving endings ever committed to the small-screen.

More recently, the children’s author, Michael Morpurgo has seen his novel War Horse adapted into both an award-winning play, and a Steven Spielberg film (in 2011). But, it is Private Peaceful (adapted for cinema in 2012), which is the most savage in its criticism of the virtual destruction of a generation of young men.

For almost 100 years, different media have attempted to explain and understand the seismic event of the Great War; the battlefield has moved from Fampoux to film, books, television documentaries and now videogames. The truth we do have is in those few seconds of flickering film at Southampton docks, and a small sundial in a park in Winton.

Bournemouth University

Bournemouth University