By Shelley Broomfield and Andrew Callaway, Lecturers in Performance Analysis

22nd August marks the 50th anniversary of the first broadcast of Match of the Day, a show that brings top class football to the masses. Over the last 50 years the show has changed a lot, but one way in which it continues to evolve is through the way it analyses performance.

Research has shown that Physical Education students can recall around 42% of sporting actions in a football match, and experienced coaches can recall around 60% of a football match (Franks and Miller 1986; Laird and Waters 2008). This shows that even experienced coaches are not recalling 40% of what happens in a match, often focusing on key events such as penalties or fouls, and their recall can even be incorrect in cases where decisions go against their team. For regular Match of the Day fans this may not come as much of a surprise, as coaches of teams disagree on the malice in a tackle or the validity of a penalty.

These studies amongst many others into the need for enhancing coach recall demonstrate the value of objective observations to allow for critical, meaningful, feedback to the coach and ultimately the players. These objective observations have been used in team and racket sports for many decades but more recently have come to be known as Performance Analysis – and have migrated to other sports too.

Performance analysis is the investigation of sporting performance, with the aim being to develop an understanding of sports that can inform decision-making, enhance performance and inform the coaching process, through the means of objective data collection and feedback.

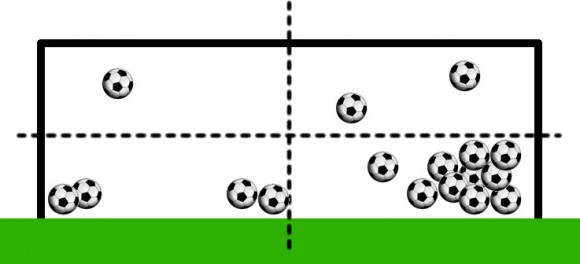

Within football, we have seen this used to great effect to improve the tactics employed by teams. An example where this can be clearly seen is through penalty kicks. In this instance a goal keeper can be shown a picture of a goal mouth with markings showing where the player most often kicks the ball. The goal keeper can use this information to help the decision making process as to which direction he is going to dive. As can be seen in Figure 1, the player kicks most often to their bottom right, so if in doubt, this is the direction the goal keeper will dive.

Recent news reports have shown that Premier League managers are taking these methods seriously. New Manchester United manager Louis Van Gaal has even had cameras installed at the clubs training ground to analyse and catalogue performance during training sessions.

Performance analysis is frequently seen during Match of the Day post-match discussion. We watch Gary Lineker in conversation with several experts, often past professional footballers and or managers, deciding whether the game was good or bad. This is a format that Match of the Day has used over a number of years. Even as recently as the 90’s this discussion was supported by video evidence from the game. However, this was limited to slow-motion video replay from minimal video angle choices. This meant the discussions around topics such as, “was a player off side?”, were often met with a lack of evidence from the video available and therefore the answer often remained inconclusive.

Move on two decades and technology has developed beyond the imagination of Match of the Day commentators from the 90’s and earlier. Match statistics are now rolling across the screen with regularity allowing spectators to clearly see the strengths and weaknesses of the teams playing. With multiple camera angles, no area of the pitch is out of the viewers or commentators reach. These camera angles are used to great effect in the post-match discussions where questions such as, “was a player off side?”, are now easily answerable with on-video graphics such as lines, circles and highlights to evidence the argument, as can be seen in the clip below.

This use of technology on easily accessible television programmes such as Match of the Day makes the average spectator an arm-chair performance analyst. Using this information, the average Joe working a 9-5 desk job can also be a Premiership football team manager in their own fantasy football league. Assuming Match of the Day keeps up with the technological advances available they will be securing their place in the hearts and homes of football spectators for another 50 years.

Bournemouth University

Bournemouth University